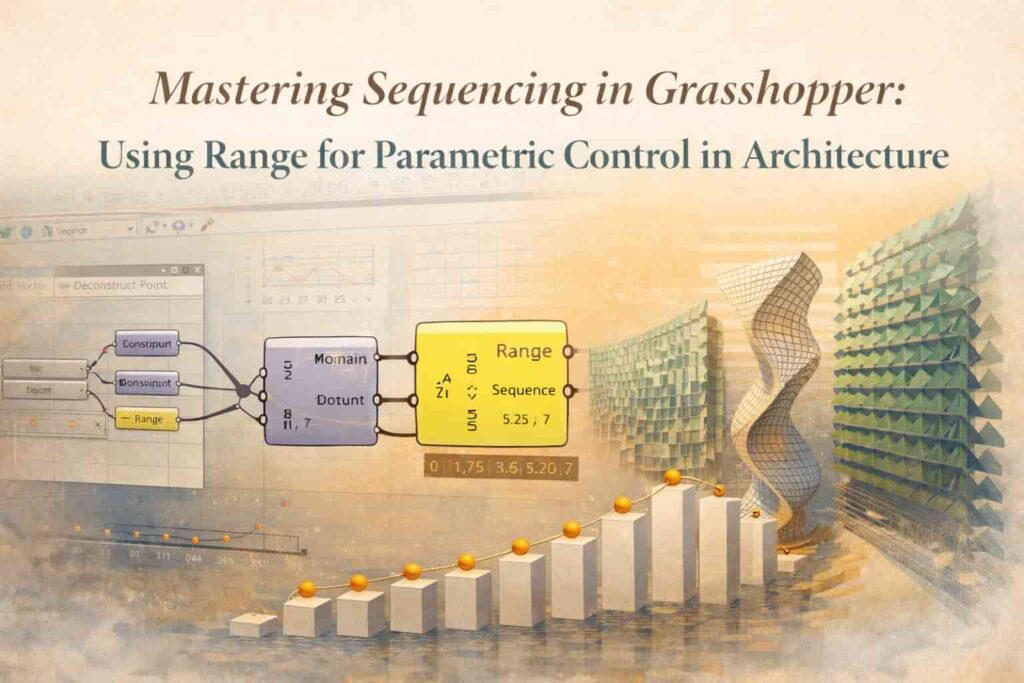

Mastering Sequencing in Grasshopper: Using Range for Parametric Control in Architecture

Introduction

Parametric design relies heavily on how data is generated, ordered, and controlled. In Grasshopper, geometry is rarely created in isolation; instead, it emerges from sequences of values that define positions, repetitions, variations, and transformations. Among the fundamental tools used to control such sequences, the Range component plays a crucial role.

Range is often introduced early in parametric workflows, yet its true potential is frequently underestimated. When understood properly, it becomes a powerful method for controlling rhythm, proportion, repetition, and gradation in architectural design. From façade modulation to structural grids and spatial organization, Range acts as a numerical backbone for parametric systems.

Understanding Sequencing in Parametric Design

Sequencing refers to the ordered generation of values that drive parametric relationships. In architectural workflows, these sequences may control distances, heights, angles, divisions, or transformation steps. Rather than manually defining each value, designers rely on mathematical logic to produce consistent yet flexible results.

In Grasshopper, sequencing allows architecture to move from static composition to dynamic systems. A single sequence can define how elements repeat, how they grow or shrink, and how variation is introduced across a surface or space. This approach mirrors architectural thinking, where order and variation coexist.

What the Range Component Does

The Range component generates a list of evenly distributed numbers between a defined start and end value. Instead of creating geometry directly, it produces numerical data that can later be mapped to dimensions, movement, scaling, rotation, or patterning.

At its core, Range answers a simple but powerful question: How do values transition from one state to another?

This transition is what makes Range so effective in architectural applications.

The component typically involves:

Read Also

Architectural Applications of Range-Based Sequencing

In architectural design, Range becomes meaningful when numbers are translated into spatial or formal outcomes. For example, a sequence of values can define how façade panels gradually change depth, how columns increase in spacing, or how roof elements respond to environmental conditions.

Because Range produces evenly distributed values, it is particularly useful when architectural elements need controlled regularity with the option for gradual variation. This balance between order and flexibility is central to parametric architecture.

Common architectural uses include:

Range as a Tool for Design Control

One of the most important aspects of using Range is design control. By adjusting just a few inputs, an architect can instantly test multiple spatial configurations. Increasing or decreasing the count changes density, while modifying the domain alters scale or intensity.

This allows designers to explore alternatives quickly without rebuilding geometry. Instead of drawing multiple versions, the logic remains constant while outcomes adapt. Such workflows encourage exploration while maintaining conceptual clarity.

Range also integrates seamlessly with other components such as Graph Mapper, Series, and mathematical expressions, expanding its usefulness far beyond basic sequencing.

From Numbers to Spatial Logic

What makes Range particularly valuable in architecture is its ability to convert abstract numbers into spatial logic. When numerical sequences are linked to movement, transformation, or dimension, they begin to express architectural intent.

For instance, a linear range mapped to vertical movement can create stepped sections or sloping forms. When mapped to rotation, it can generate twisting towers or dynamic roof structures. In this way, Range becomes less of a mathematical tool and more of a design language.

Avoiding Common Misunderstandings

Many beginners use Range only as a subdivision tool, without fully understanding its role in data flow. This often leads to confusion when outputs do not match expectations. The key is to remember that Range produces values, not geometry.

Clarity improves when designers consciously decide what each value represents—distance, angle, scale, or proportion. Once this relationship is clear, sequencing becomes intuitive rather than mechanical.

Why Range Is Fundamental in Parametric Architecture

Parametric architecture depends on systems that can adapt while remaining coherent. Range supports this by introducing controlled continuity into design logic. It enables architecture to respond systematically rather than arbitrarily.

By mastering Range-based sequencing, designers gain the ability to:

These qualities are essential for contemporary architectural practice, where performance, efficiency, and expression must align.

Conclusion

Sequencing using Range is not just a Grasshopper technique—it is a way of thinking about architecture through relationships and transitions. When used thoughtfully, Range allows designers to move beyond static forms and develop responsive architectural systems grounded in logic and clarity.

For architecture students and professionals alike, understanding Range is a critical step toward mastering parametric design. It transforms numbers into structure, logic into form, and experimentation into meaningful architectural outcomes.

References

- Woodbury, R. Elements of Parametric Design

- Ching, F. D. K. Architecture: Form, Space, and Order

- Tedeschi, A. AAD_Algorithms-Aided Design

- Grasshopper Official Documentation